An examination of how wasifills—a component adapter pattern like polyfills, but for

components—can help bridge the gap between today's rapidly changing standards landscape and the

future of interoperable components facilitated with wit and wit worlds. It's an amazing time to

be on the bleeding edge of the WebAssembly adoption curve, but it's not without risk.

The developer's journey to Mordor via WebAssembly has a fairly predictable pattern. First, we discover that Wasm could be a powerful ally in our battle against the empire, so we start researching. The first thing we figure out how to do is exchange numbers between the host and the guest. The relationship between host and guest in WebAssembly is a simple one: a host provides functions the guest can call, and the guest provides functions the host can call. These functions can only ever accept and return numbers.

Once we know how to cross the host-guest boundary, we write an add function and can call it from

the wasmtime CLI or even JavaScript in a browser. This rekindles long extinguished fires in the

brain and we decide that we need to explore further.

Next, we wonder how we can exchange more robust data like full structs, blobs, and more. This is

where our journey leaves the well-trod road and we find ourselves somewhere in the swamp of despair.

This feels like uncharted territory with no way out, but we soon discover that instead of it being

uncharted, there are hundreds of different paths and no guide as to which one to take.

Contract-Driven Development

Some products solve this problem by trading wasm32-unknown-unknown (the so-called "freestanding"

modules) for WASI. Here they use the access to stdio available in WASI to exchange opaque data

blobs across the I/O pipe. Other products and frameworks come up with their own way of marshaling

data across the boundary (you may see these called ABIs or "application binary interface") and

build proprietary libraries on top of those interfaces. For example,

Open Policy Agent lets you compile policies

into WebAssembly, and the interface between guest and host is specific to OPA. "Legacy" wasmCloud is

also a custom library-style interface that relies on a fixed set of imports and exports.

The combination of a Wasm module's imports and exports represents an explicit contract between that module and its host. One huge benefit of contract-driven development is the loose coupling and flexibility we gain in exchange for the up-front cost of contract design. But is WebAssembly ready for this kind of loose coupling across the guest/host boundary?

The short answer is yes, but the reality is that out here on the bleeding edge, there are exceptions. Standards are changing and features are rapidly appearing in WebAssembly engines seemingly every other day. WebAssembly components and the component model are the solution to this problem, but the component model is still volatile, so we need something to insulate us from that volatility while we build products. The alternative is to simply step back and wait until the lava flow hardens, but then we miss out on all the benefits of early adoption.

For the rest of this post, I'm going to talk about a pattern for building applications this far out on the adoption curve while being able to enforce some measure of control on the underlying standards: wasifills.

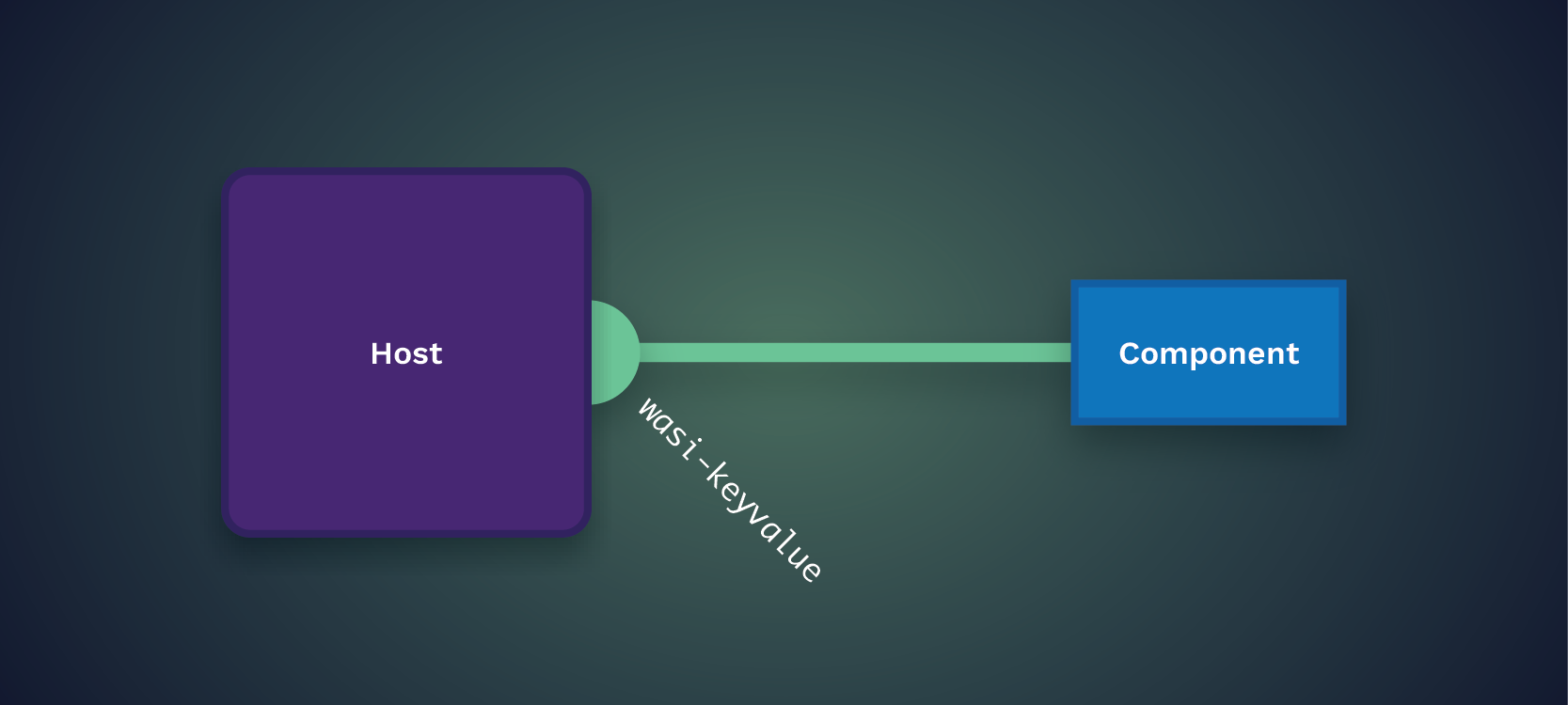

Components let us snap together pieces of code that communicate via interface rather than tight coupling. A component doesn't have a compile-time dependency on the actual implementation of another component, it only knows how to communicate across the contract boundary. More importantly, the "thing" on the other side of that contract can be either another component or the host itself.

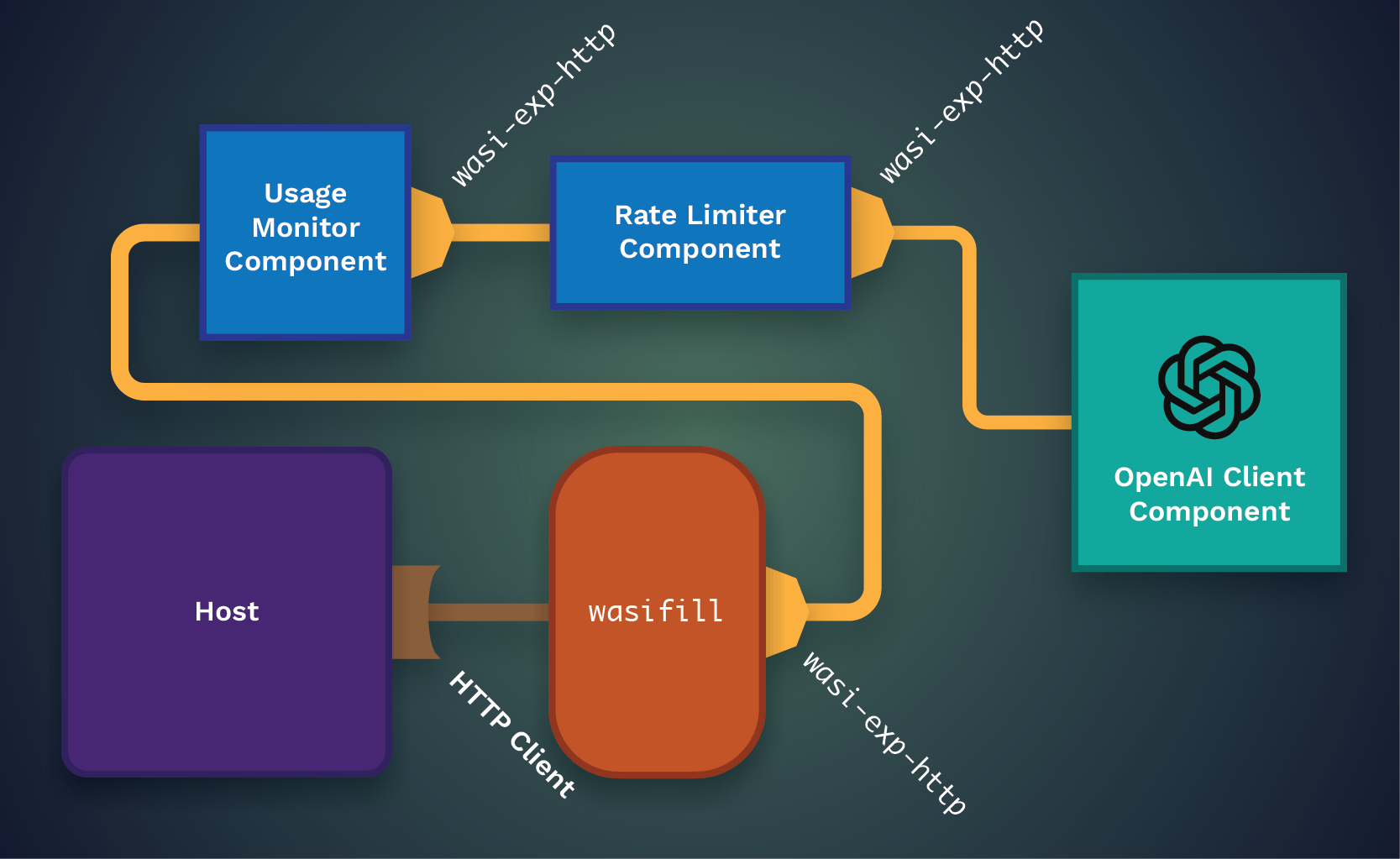

For example, in the following diagram, we have a component that makes use of the current version of

the wasi-keyvalue contract:

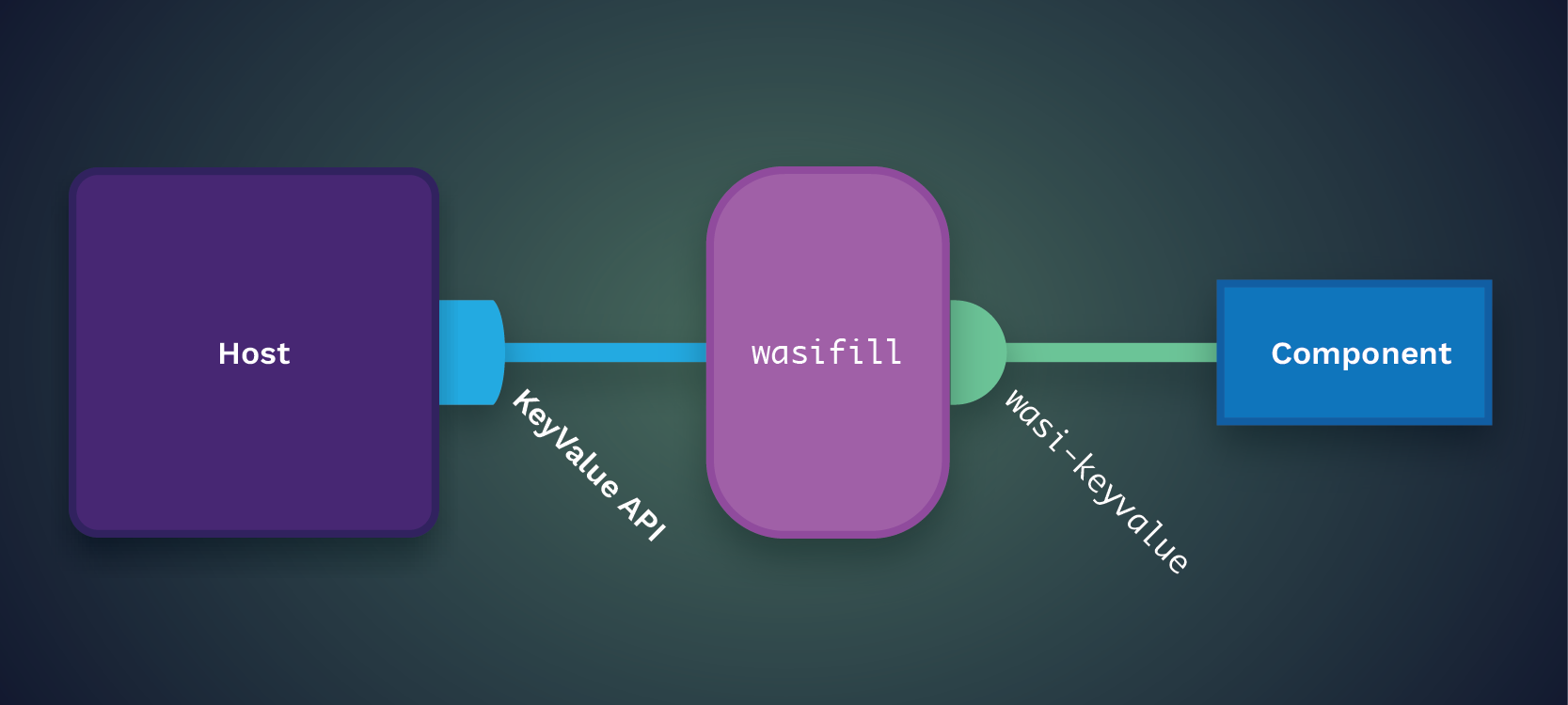

This is great, but I can currently count on 0 fingers the number of hosts that natively support

the current wasi-keyvalue contract. So how do we get started building things out of components if

our hosts can't speak the component language? Finally, we get to talk about wasifills. If you've

heard of the term polyfill, then you

know it is a piece of code used to provide modern functionality on older browsers. In essence, there

are two sides to a polyfill: one modern and one legacy. The polyfill code translates between the old

and new worlds. Other names for polyfills and polyfill-like code might be proxy, adapter, or

middleware.

A wasifill provides bleeding-edge component functionality to component developers while still

supporting legacy interfaces. Let's assume that our host doesn't know how to speak wasi-keyvalue,

but it does support a legacy contract that can be used to make requests of a key-value store. In the

following diagram, you'll see how we can insert a wasifill in a way that leaves our component code

blissfully unaware of what the host does or does not support. As the host evolves, so too can the

wasifill without us having to rewrite any component code.

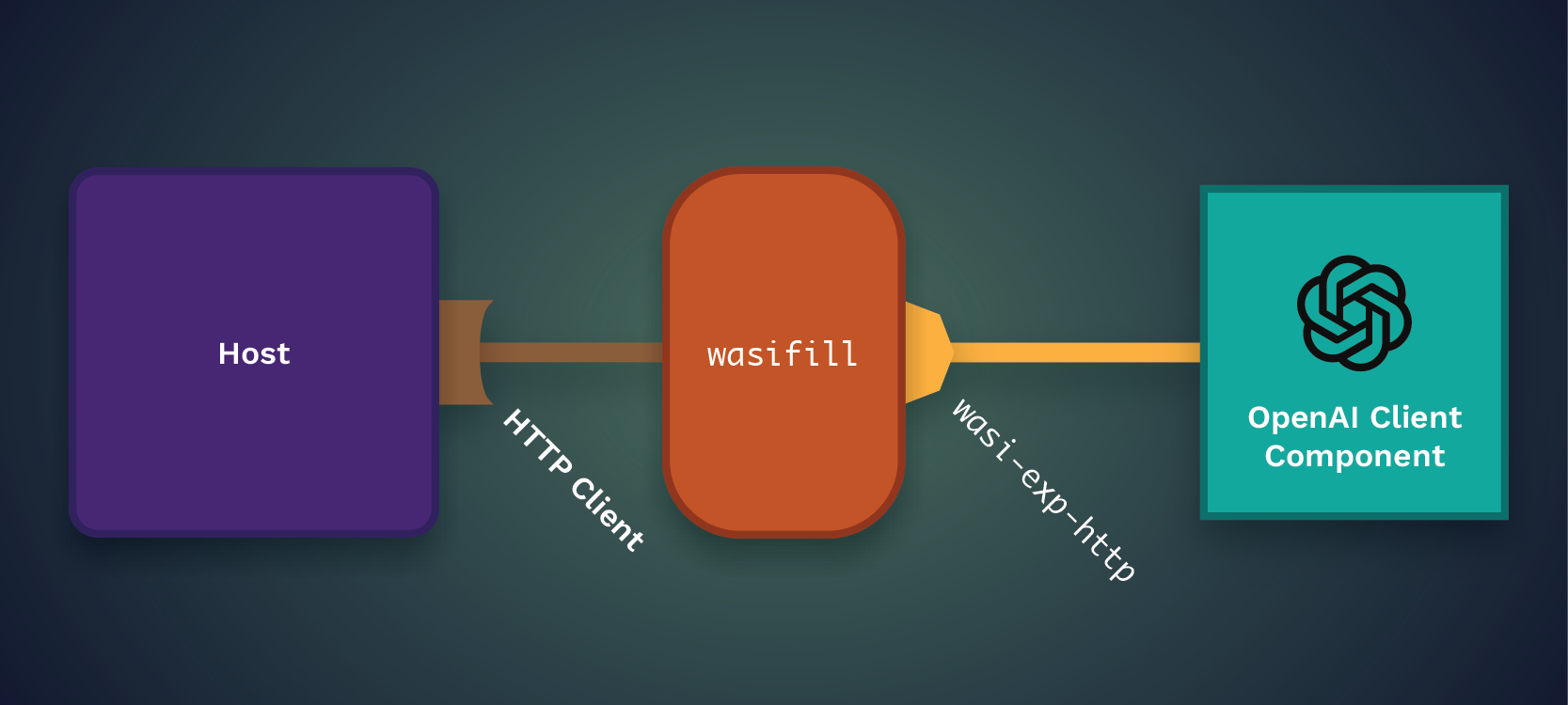

There are uses for wasifills above and beyond translating between old and new worlds. We can use

them to truly extract every ounce of power out of components. Let's say we've built a component that

communicates with the Open AI API. If we're using HTTP for this, we know we'll need to make use of

an HTTP client (let's call it wasi-exp-http to avoid rabbit-holing on the ever-changing

standards). The following diagram shows our component code going through a wasi-exp-http wasifill

to reach the host. Our code may also need to make other HTTP requests that are not part of Open AI.

This is probably fine for local testing, but production is something else entirely. Using the Open AI API isn't free once you go beyond a few experiments. We want to make sure that we limit the use of this API without inhibiting other calls. While we're at it, we might also want to keep track of component network usage regardless of whether it talks to Open AI. In the next diagram, we've used wasifills to bolt two new components between our real code and the host: a rate limiter that can control access to Open AI, and a usage tracker that monitors all outbound HTTP calls, ending the chain in a wasifill that allows this code to run on an "old" host.

Our code remains unaware of how many intervening components (wasifill or otherwise) there are between it and the host. Our code can run unaltered in local and test environments, and then run with middleware and no wasifill on a "modern" host, and run with middleware and wasifills in a production environment; all without changing the code.

Wrapping Up

The distillation of this post is that you can start to work with Wasm components today. While it

might be high friction, it's possible through the use of wasifills insulating us from the volatile

standards and runtime changes below. As the Wasm ecosystem marches toward the ultimate goal of

"everything speaks wit", we can gradually remove more and more wasifills, until we're ultimately

left with our component and whatever middleware our target runtime wants to inject.

The rest of this year in the world of WebAssembly is going to be incredibly exciting. We are rapidly approaching a world where nobody mentions WebAssembly when they're building their applications: they just write what they need and Wasm resigns itself to an implementation detail made insignificant through tooling and standards.